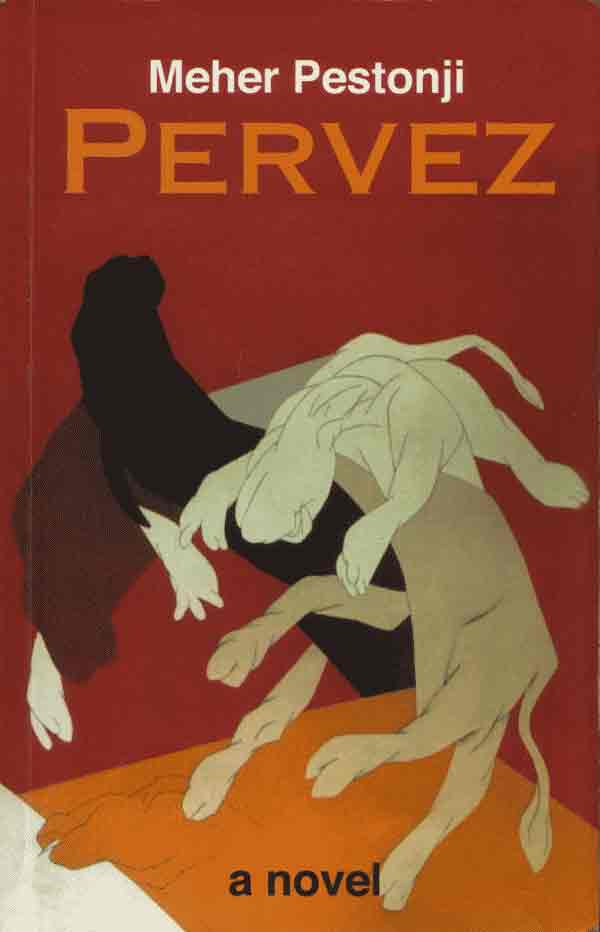

An Indian novel in

English that takes politics and activism as its subject is rare; one that treats

this subject with positive conviction instead of cynicism is rarer still. So,

just the fact that Pervez , activist-journalist Meher Pestonji’s first

novel, traces the response of a young woman to the spiraling communal violence,

from Bombay’s holocaust in 1992 to Gujarat’s a decade later, would

make it refreshing enough. What makes reading it a real pleasure is the sensitivity

and lightness of touch with which the novel explores a range of contemporary

political issues – without appearing in the least didactic or self-righteous.

An Indian novel in

English that takes politics and activism as its subject is rare; one that treats

this subject with positive conviction instead of cynicism is rarer still. So,

just the fact that Pervez , activist-journalist Meher Pestonji’s first

novel, traces the response of a young woman to the spiraling communal violence,

from Bombay’s holocaust in 1992 to Gujarat’s a decade later, would

make it refreshing enough. What makes reading it a real pleasure is the sensitivity

and lightness of touch with which the novel explores a range of contemporary

political issues – without appearing in the least didactic or self-righteous.

Pervez is the story of a young Parsi woman, returning to Mumbai after a failed marriage to a Goan Catholic, who is both attracted and repelled by the values of her friend Naina’s circle of left-secular activists. Gradually, as she confronts all the attitudes she has unconsciously imbibed with her elite background, she is drawn into activism in the tumultuous months preceding the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

As the novel unfolds, Pervez’s misgivings on meeting the activists are mirrored by our own: will the characters be stereotypes, spouting clichéd diatribes? It is pleasant to find these doubts unfounded; the narrative is energetic and unforced, the characters are convincing and hold one’s interest with no effort. Even as a range of issues – communal politics, Ayodhya, the Shahbano case, reservations – are ‘explained’ to the novice Pervez, the dialogue and narrative avoid seeming artificial or text-bookish.

Naina’s partner, the Marxist Sidharth taunts Pervez for her wealth, her class position and her political naiveté. She meets surprises in her community and class – her brother is staunchly liberal but disappoints her by stopping short of actively supporting political causes. She finds communal violence and cruelty in the slum Shiv Sainik as well as in her brother’s rich client Vasant Chawla. She is fearful of facing the poverty of the slum of Dharavi – but, to her surprise, meets a relative of one of her former in-laws there. She realizes how her marriage had outraged her parents for having broken the laws of class, not just of community. Even within the wealthy Parsi community, she finds poverty in a destitute aunt dependent on charity.

What disturbs her most is the fact that the tiny, parochial Parsi community, which perceives itself as superior and neutral, holds deep-seated, irrational, anti-Muslim prejudices as much as the Hindu community!

Pervez develops a tentative friendship with a young Dharavi boy Munawar. Repelled by the fact that Munawar has been rioting, she is gradually forced to question if his retaliation is understandable, though not justifiable. Meeting riot victim children in Gujarat, she recognizes that the scars of a communal pogrom may “never heal…that each surviving victim held the seeds of a potential terrorist”.

The novel weaves in issues of gender and caste most naturally. The dalit activist from Dharavi, Vishal, is a poet and a moving singer, who along with Munawar’s brother Saeed challenges communal forces in Dharavi. But when Munawar is stabbed, Saeed refuses Vishal’s offer to donate blood, because as Vishal bitterly realizes, “he doesn’t want his brother to receive a Mahar’s blood.”

Pervez’s own comprehension of her own sexuality, love, appetites, tenderness, friendship and trust forms a running thread in the novel. Through the character of Vandana, the knotty issues of feminism are explored. A girlfriend of one of Naina’s friends, this small town girl’s only ambition is to be a fashion model posing in the nude or a film star. She challenges the others – they talk of freedom, but why do they not let her be ‘free’ to market her sexuality? The feminists grapple in vain with the problem of persuading a small town girl that modeling is not liberating but exploitative. More troubling to Pervez is the unconscious gender stereotyping among the activists: to her irritation, Naina invariably does the cooking and makes tea, “like an obedient wife”.

Pestonji’s portrayal of Sidharth the ‘Marxist’ is mixed. On the one hand, Pervez is shown to admire his sensitivity, skill and courage in dealing with explosive and complicated situations and people. But why, then, are his utterances on ‘class’, ‘declassing’ etc…made to smack of an immature and crudely oversimplified understanding of Marxism, which is dogmatic to the point of being laughable? Is it because, in Bombay’s university circles, it is this kind of anarchist radical intellectual who, more often than not, passes off for being ‘Marxist’?

Pervez successfully captures the transformation of Bombay’s cosmopolitan ethos, in the course of the ‘90s, into the narrow,commercialized, insensitive ‘Yeh Dil Mange More’ ethos of today’s Mumbai. It also mirrors the anguish, and concern of middle class urban intelligentsia about communalism. Pervez recalls the energetic dharnas of 92-93, and feels the dharna against the Gujarat carnage ten years down the line, has “depressed, not energized her”. Modi remains in power, and she finds the delayed protest of the “powerful citizens” a “flaccid response to genocide”. But there is no room for cynical disillusionment. Pervez tempers her rage at the “ helplessness of civil society” with the thought that such protests will continue to be important, relevant.

The novel shows an awareness of the problematic nature of the Gandhian “communal harmony” framework, while sharing its basic ethos. A well-intentioned student of Pervez’s composes a hymn – ‘He Bhagwan, O Allah, Shanti Do’, and tries to get people in a riot victims’ camp to join her in singing it. But the victims of the communal pogrom are disturbed, suspecting that yet again they are being coerced into saying ‘He Bhagwan’ or ‘Jai Shri Ram’. Dramatically, we are given an insight into how a beleaguered and insecure minority might justifiably feel alienated by the ‘Ishwar Allah Tero Naam’ idiom. Yet, this is the idiom that comforts the anti-communal activist – even Pervez, at the end of the novel, hums the hymn to herself.

For many, the period surrounding the Babri Masjid demolition was a politically formative one. Being one of those who, as a student in Bombay, first felt the impulse for activism during the horror of the riots of 1992, I can fully appreciate Pestonji’s skill in evoking that turbulent phase. Not least of her achievements is to have succeeded in conveying a sense of deep personal concerns (for instance regarding the Parsi community) in a novel embedded in politics. This novel, written with a spirit of urgency and deep concern, invites the reader to overcome the natural middle-class tendency to ignore the disturbing reality of contemporary politics. I hope it will succeed in inspiring at least some like Pervez to take a step in the direction of social concern and commitment! -- Kavita Krishnan