“…the current crisis differs from the various financial crises that preceded it. …the explosion of the US housing bubble acted as the detonator for a much larger "super-bubble" that has been developing since the 1980s. The underlying trend in the super-bubble has been the ever-increasing use of credit and leverage. Credit—whether extended to consumers or speculators or banks—has been growing at a much faster rate than the GDP ever since the end of World War II. But the rate of growth accelerated and took on the characteristics of a bubble when it was reinforced by a misconception that became dominant in 1980 when Ronald Reagan became president and Margaret Thatcher was prime minister in the United Kingdom….

“The relative safety and stability of the United States, compared to the countries at the periphery, allowed the United States to suck up the savings of the rest of the world and run a current account deficit that reached nearly 7 percent of GNP at its peak in the first quarter of 2006. …” This inevitably led to the crash, he notes. ('The Crisis and What to Do About It', The New York Review of Books, December 4, 2008)

Well, the ace speculator describes the surface froth all right, but fails to relate it to the underlying crosscurrents that work it up. He castigates deregulation and dependence on debts, but fails to explain why this highly hazardous course was adopted, and is still being adhered to, not only in the US but all over the capitalist world.

Earlier in this article we tried to understand these very questions. What we learned in theory may now be briefly recapitulated in the light of actual developments.

First, behind the familiar crisis symptoms lurks a complex interplay of myriad forces, the most important being the tendency of the average rate of profit to fall with rising organic composition of capital and increasingly skewed distribution of income and wealth. There is no dearth of data supporting this: data showing, for example, falling profit rates and stagnant/declining wage levels vis-à-vis corporate profit explosion in recent decades.

Second, the bourgeoisie's frantic endeavour to overcome these constraints leads to, apart from war economy, artificial credit- induced expansion. But this false prosperity built on debt always bounces back in the shape of sudden contraction or crisis. This is what we call a bubble – something like a rubber band stretching and snapping back. Bubbles in other words are an inevitable result of efforts to "grow the economy," by means of debt, faster than is warranted by the underlying flow of new value generated in production. Such was largely the case with the "roaring twenties” that preceded the harbinger of the Great Depression -- the Wall Street crash of October 1929. But the more sophisticated and widespread the credit market, the greater is the degree to which "forced expansion" (as Marx called it) can be induced and the more devastating must be the inevitable crash whenever it comes. This is precisely what we see happening today. The survival strategy of betting on rampant financialisation, aided by neoliberal deregulation and globalisation, yielded almost miraculous results in the US, where it was applied in the most extensive and innovative way. And that was why the global chain of "rubber bands" snapped precisely at that weakest link.

Third, crises constitute capitalism's inbuilt mechanism for ruthlessly eliminating excess or over-accumulated capital, so that "the cycle would run its course anew." But the exact trajectory of this progression depends on the peculiar features and severity of a particular crisis as well as other attending factors, both economic and political. The fierce fight among capitals (big corporations) and national blocks of capital (nation states) that a crisis engenders may, for example, lead to local or global wars. Thus the Great Depression of 1930s (GD) was normally overcome by the mid-1930s only in part; for the rest, it produced fascism and led to -- or should we say merged into -- the Second World War. What will happen this time round nobody can tell at this point in time, but surely it is possible, and worthwhile, to indicate some broad trends and possible scenarios.

CRISIS ENGULFS THE EMPIRE

The US economy shed 533,000 jobs in November -- the largest monthly job loss since December 1974 -- bringing the year's total to 1.9 million. The latter figure surpasses the 1.6 million jobs lost in the 2001 recession. The National Bureau of Economic Research has announced that a contraction had actually begun in December 2007, the month payrolls peaked. At 12 months, the recession is already the longest since the 16-month slump that ended in November 1982.

A Quick Look at the Backdrop

How did this particular crisis set in?

With the "dot.com" or “New Economy” stock market bubble burst in 2000, the US economy went into recession and it was weakened further by the 9/11 attacks. In order to allay the fears of financial collapse, the Federal Reserve lowered short-term interest rates. But employment kept falling through the middle of 2003, so the Fed kept lowering short-term lending rates. For three full years, starting in October of 2002, the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) federal funds rate was actually negative. This allowed banks to borrow funds from other banks, lend them out, and then pay back less than they had borrowed once inflation was taken into account. This "cheap money, easy credit" strategy created a new bubble – this time based in home mortgages. This “great bubble transfer" involved a further expansion of consumer debt and an enormous profit explosion in the finance sector achieved through extension of mortgage financing to riskier and riskier customers. There were lots of what insiders call "ninja" loans — no income, no job, no questions asked. As Martin Wolf of the Financial Times aptly observed, "The US itself looks almost like a giant hedge fund. The profits of financial companies jumped from below 5 per cent of total corporate profits, after tax, in 1982 to 41 per cent in 2007."

Monthly Review editor J. B. Foster gives us a penetrating analysis of the situation:

“…the theory [was that] new "risk management" techniques had devised the means (hailed -- bizarrely -- by some as the equivalent of the great technological advances in the real economy) with which to separate the weaker from the stronger debts within the new securities. These new debt securities were then "insured" against default by such means as credit-debt swaps, supposedly reducing risk still further.”

But this proved illusory and the devastation started. The payments on subprime debt faltered, slowly at first, then in a massive way. The other side of the problem was that, “as a result of the completely opaque securitization process, no one knew which debts were bad and which were good. Credit markets froze because the banks and other financial institutions were ceasing to lend since the borrowers could not be counted on to pay them back. …

"Under these circumstances, no matter how many hundreds of billions of dollars in liquidity were poured into the financial sector, nothing happened. All those with money, including the banks, were hoarding. The U.S. was printing dollars like mad and flooding the financial sector with liquidity, but rather than loaning out money capital the banks were stuffing it in their vaults, or more precisely using it to purchase Treasury bills, creating a kind of revolving door that negated the attempts of the government.” For the time being “a complete meltdown” was prevented “by injecting capital directly into banks in return for preferred stock (a partial nationalization of banks), guaranteeing new debt of banks, and increasing deposit insurance.2" [Monthly Review October 10, 2008] But thanks to a secular collapse of confidence, money markets remained tight and recession continued to deepen.

Bailout Blues

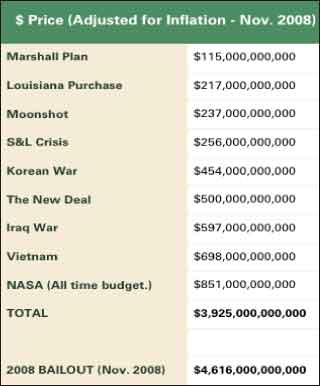

The salvation plan dished out by the Bush Administration is remarkable both for its sheer size and the opposition it has evoked. Take an assessment, comparing the bailout with other large US Govt projects, given by frequent CNBC commentator, Barry Ritholtz on his blog (see table on p 19).

It should be noted that Ritholtz’s figure of $4.6165 trillion as total bailout amount might be an understatement. According to New York Times (October 18, 2008) the all inclusive bailout figure was already "an estimated $5.1 trillion” by October -- and it is growing!

As widely reported in the press, the "Emergency Economic Stabilisation Act of 2008" was passed in the face of tremendous opposition. At one time, calls and emails from constituents to the Congress were running as high as 300 to 1 against the bailout. There were many street demonstrations too. Some 400 economists, including two Nobel prize winners, opposed it, which was then 'sweetened' in the Senate by another $110 billion in tax relief and renewable energy incentives to get enough House vote for passage.

The basic opposition against the bailout is that it transfers huge amounts of public money into the hands of private financiers responsible for the catastrophe instead of punishing them and leads to a spiralling public debt. The message goes out that the executive fat cats of Wall Street can earn themselves royal fortunes through reckless -- often illegal -- business practices and then get away scot-free when their firms go down, bringing untold miseries to their customers. Economists have also pointed out that at bottom it is more a problem of solvency than a mere credit crunch. The assets of colossal financial institutions have depreciated in a big way on account of massive fall in the value of the loans (including securitized loans) they have advanced. Therefore, flooding the system with debt liquidity will not help; it may indeed be counter-productive.

Even the actual implementation of the $700bn bail-out of the US banking system has already been seriously questioned by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). It is being carried out without adequate oversight and monitoring, the Congressional watchdog observed, and added that the Treasury "has no policies or procedures in place for ensuring the institutions... are using the capital investments in a manner that helps meet the purposes of the act."

Crisis and Obamanomics

"... few are discussing a more intangible, yet potentially much greater cost [compared with the economic cost -- AS] to the United States — the damage that the financial meltdown is doing to America's "brand" -- lamented Francis Fukuyama (FF) in a Newsweek article exactly a month before the US presidential election. Here is what he meant by "America's brand ":

"Ideas are one of our most important exports, and two fundamentally American ideas have dominated global thinking since the early 1980s …The first was a certain vision of capitalism — one that argued low taxes, light regulation and a pared-back government would be the engine for economic growth. …The second big idea was America as a promoter of liberal democracy around the world, which was seen as the best path to a more prosperous and open international order." Thanks to the Iraq misadventure followed by the financial crisis, both these pillars of American hegemony have been all but demolished, complained FF. The learned professor, who had triumphantly declared the "End of History" (that is, the final victory of capitalism and liberal democracy) in early 1990s, has therefore started talking in terms of “The End of America Inc." (as the title of this article goes) and "the post-American century". The overwhelming majority of American intellectuals shared his disappointment. In a representative tract caustically titled The Return of History and the End of Dreams, noted right-wing author Robert Kagan gave vent to his bitter feelings.

In this gloomy backdrop, the election of a very popular president has appeared as a much-needed political bailout package for the American elite. The day after the election, the Washington Post delightedly wrote that “America had produced . . . inspiring and overdue proof that the American dream was still alive."

Will the euphoria, which was shared by practically the whole of the corporate media, translate into easing of people's economic woes and reconsolidation of American hegemony? No sensible economist or analyst, including supporters of the president-elect, seems to be in a position to claim that.

Obama has dropped some broad hints about his priorities, e.g., "a new energy economy", which might imply incentives to atomic as well as renewable energy industries, and large scale job creation “by making the single largest new investment in our national infrastructure since the creation of the federal highway system in the 1950s". What all this will actually amount to remains to be seen, but it appears the President-elect will have to do a very tough tightrope walking between the aroused aspirations of the "the small people" and the interests of his corporate sponsors. It may be noted in passing that US big business contributed much more to his campaign funds than to his Republican contender’s (see details in “Obama and 'Change': A Letter from the US”, Liberation, December 2008); it also appears that the Obama appointments indicate more of a continuity of policymakers than of change.

The prospects of the US economy coming out of what Paul Krugman calls "depression economics” appear even bleaker when considered in the context of the chronic deterioration of the economic fundamentals: growing fiscal and budget deficits, persistently declining competitiveness of US industries, unbearable costs of the Iraq war, the weakening dollar, and so on, to name only the more glaring distortions. In the 1970s Americans had a savings rate of over 10%. Now, it is zero. In the 1970s America still had a very strong manufacturing sector. Now it is down to less than 15% of US GDP. Most important, US leadership of the capitalist world has long been exercised through Wall Street's status of being the undisputed centre of international finance with the dollar as the international currency. The recent blow has badly weakened that. Of course, no single currency is yet in a position to completely replace the dollar as international medium of exchange. But a partial shift to the euro and other hard currencies had already begun since the early years of this century and, depending on how the crisis plays itself out, this trend may grow and threaten the rule of King Dollar.

CRISIS AND WORLD ORDER

The way the financial tsunami is generating tidal waves and leading to job losses all over the world is widely reported in the press every day; so let us just take note of certain cardinal facts and features.

World trade is projected to fall next year for the first time since 1982 and capital flows to developing countries predicted to plunge 50 percent, the World Bank said in a forecast released 9 November. Developing countries will grow at an average rate of 4.5 percent next year — a pace that almost constituted a recession, given the need of these countries to grow rapidly to generate enough jobs for their swelling populations. "You don't need negative growth in developing countries to have a situation that feels like a recession," said Hans Timmer, who directs the bank's international economic analyses and projections. As the World Bank's experts struggled to find a historical parallel to the slump, they said it had more in common with the GD than with the severe recessions of the 1970s or 1980s. Meanwhile, authorities in Greece are battling violent street protests in Athens and other cities, caused in part by the deteriorating economy.

As for the responses till the time of writing (early December 2008), finance ministers from all 27 European Union countries met to discuss proposals for a stimulus plan totalling 200 billion euros (250 billion dollars) even as China launched an economic stimulus package worth nearly $600 billion. Central banks in U.S. and Europe are heading towards zero interest rates. In India a series of stimulus packages including interest rate cuts have been announced to arrest the pronounced downturn, with hardly any tangible results.

Further Centralisation of Capital

As a rule, during a crisis big fish eats small fish and mergers of corporate biggies also take place. Recent examples include JP Morgan Chase’s purchase of Washington Mutual and Bear Stearns, and Bank of America’s absorption of Countrywide and Merrill Lynch. In many cases the US government has encouraged or even forced such mergers, the most well-known being the acquisition of Merrill Lynch by Bank of America. Both of them have received funds under the Treasury's Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) established as part of the $700 billion bailout of the financial services industry. All of this is creating a more monopolistic banking sector with government support. At the losing end, as always, are the workers and employees: Bank of America has already announced plans to slash up to 35,000 jobs over the next three years.

At the present moment mergers and acquisitions in most other sectors are at low ebb. But if past experience is any guide, we are likely to see big moves in steel, automobile and other industries in the not too distant future. In some segments – e.g., the IT-related security industry – this has already begun. As Kelly Jackson Higgins reports in Information Week Business Technology Network, December 9, 2008, “Cold economy [is] a hot time for firms to either buy their way into new technologies and expand, or [for smaller and less established firms] to merge and bulk up.”

While all this is “normal practice”, there are certain new features which, according to some commentators, make the current crisis potentially more devastating than the GD.

Unprecedented Sweep

Thanks to successful globalisation, this time around there is no country like the erstwhile Soviet Union to escape from the crisis. It is spreading, thanks again to highly efficient networking by IT-enabled services, at electronic speed all across the planet. The huge flows of capital across national borders led to large- scale currency crises in recent decades, and now these have assumed fatal proportions.

Two more dimensions of the scale and depth of the crisis need to be noted.

As Bangladeshi Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus pointed out in an interview in London, “What we see as a financial crisis is a part of many more crises, which are going on simultaneously in 2008”. He was referring to the food, energy and environment crises. Indeed, with rising joblessness food availability for some 90% of world operation will decline further, adding to what Lenin once called "inflammable material in world politics". The recent drop in petroleum prices is not an unmixed blessing either. For one, it will reduce consumption in exporting countries. Moreover, while the present price level indicates the unsavoury role of speculative trading during the earlier period of rising prices, it also constitutes probably the most telling confirmation of falling demand with falling industrial and commercial activities. Again, financial difficulties will prompt corporations and nations to put on hold costly climate protection measures. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has warned the world against backsliding in the fight against climate change as it battles the financial crisis, saying "When the world has recovered from the economic recession, it will not have recovered from climate change".

Secondly, like the present crisis, the GD also was "made in US". But when the latter struck, the US was already in the first phase of gaining economic supremacy in the capitalist world and it was not assailed by any political or military crisis. In the present case, that country was already in a phase of slow, long-term decline in economic prowess (measured in terms of share in world GDP, trade and manufactures; savings rate etc) particularly relative to emerging economies like China. Moreover, it is suffering from a political crisis of legitimacy and leadership while finding itself burdened with an over-extended military juggernaut and a Vietnam-like situation in Asia. The present crisis is therefore widely seen as the precursor of a shift in global power balance -- a shift towards greater multipolarity marked particularly by the rise of the East. Apart from men like Tony Blair, Ban Ki Moon and Peer Steinbruck, the US authorities too have recognised this.

Intensified Power Struggle

But this should not be understood in a mechanistic way to mean the decline of the US alone. Apart from the EU and Japan, Russia and China too are severely affected. Every nation is, and will be, fighting for itself in its own way and the results cannot be predicted. It will be interesting to watch, for example, how the dovetailed economies of "Chinamerica" -- as economic historian Niall Ferguson has called it -- respond to the crisis and which side scores greater gains at the cost of its contender-partner. Russian resurgence and the country’s capacity to challenge the US on many issues depended largely on high prices of its fuel exports and now it is in for a serious rouble trouble.

Some early indications of the struggle among world powers to shift the burden of the crisis on to one another was expected from the mid-November White House summit of heads of G20 nations. Shortly before the meeting, French President Nicolas Sarkozy said that it was necessary to rebuild the entire global financial and monetary system, "the way it was done at Bretton Woods." "Times have changed”, he added: "now the Euro and other currencies have a place in world financial exchanges, a new reality that should be reflected in new rules." Many leaders called for new rules and tougher regulations together with restructuring the IMF. But just on the eve of the Summit President Bush announced, "The crisis is not a failure of the free-market system, and the answer is not to try to reinvent that system." It would be a "terrible mistake" to allow "a few months of crisis" to undermine faith in free market capitalism, he observed. In the event it was the US position that prevailed and attempts at a new Bretton Woods system were stymied. But for a two-paragraph indictment of the United States as the perpetrator of the financial crisis, the Summit declaration remained vacuous.

However, conflicts among big powers and regional entities are growing. European leaders have met separately and the leaders of China, Japan and South Korea will hold a rare joint meeting on 13 December to try and work out how best to cushion Asia from the global economic crisis.

To sum up and conclude, we have found that the current crisis has its roots in the economic slump of the 1970s, from which the global economy never fully recovered -- not in the way in which the destruction of capital in and through the Great Depression and World War II led to a post-war boom. So in addition to war economy, financial bubbles became the chief means of countering stagnation of the “real” or productive economy. But bubbles inevitably burst, bringing the underlying economic problems back to the surface. New and bigger bubbles lead to still greater financial crises and worsening conditions of production, in what has now become a vicious cycle.

Global experience in the age of imperialism, which Lenin defined as moribund monopoly capitalism under the domination of finance capital, brilliantly confirms and enriches the Marxist-Leninist explanation of business cycles and capitalist crisis. Explanations, of course, are valuable only as stepping stones to action -- mass revolutionary action. As the Party Central Committee's "Call for the Pledge Campaign" points out, “After decades of aggressive expansion, world capitalism is passing through a period of grave crisis. … For communists and anti-imperialists who had been sought to be pushed back by the marauding offensive of corporate globalisation and imperialist war, the time has come to hit back and surge ahead.”

End notes:

1. Capital Volume 3, P 250,emphases in the original