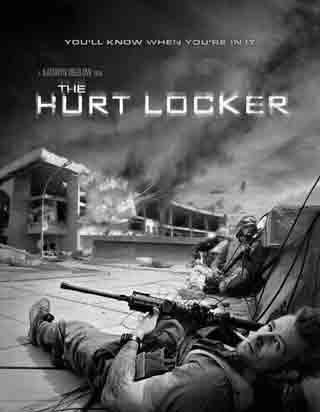

Now that the dust of the Oscars has settled, however, it seems that all the sound and fury of The Hurt Locker was nothing more than a Bush-style campaign of 'shock-and-awe': despite all the hype, the film offers very little in the way of meaningful content or message, and it is certainly not an 'anti-war film'. Far from being a critique of the Iraq war, or the rapacious politics behind it, it is a sensationalist imagining of war so removed from reality that even most American soldiers who reviewed the film called it pure 'fantasy'. So how did a film that promotes itself as an uncompromising look at the experience of war avoid actually dealing with the war at all?

Before the film's release, Bigelow declared that she had set out to make a 'non-political' film about war and those who participate in it. The suggestion that one can make a 'non-political' film about an ongoing war in which millions of Iraqis – let alone thousands of American and other soldiers – have died, and which has been exposed time and again to be nothing but a rapacious profit-making exercise for American big business, is either wildly politically irresponsible, or grossly disingenuous. A quick study of both the film and its director reveals that it is both.

Bigelow is a self-proclaimed 'post-structuralist/post-modernist' whose main interest lies in making de-constructed, dis-junctured films examining individual psychology; her training took place in the moneyed, 'high art' post-modern scene of 1980's New York, and many of her films – including The Setup, Blue Steel and Strange Days – tend to cater to the aesthetic and political sensibilities of elite consumers of high art. So when Bigelow set out to make a film that uses a horrendously destructive and universally-condemned war as nothing more than a 'backdrop' for a cinematic study of one man's psyche, her intended audience was exactly the kind of ultra-rich elites who, being far-removed from the realities of war (or even its disastrous economic effects in the US) could watch such a 'psychological thriller' without letting the unsettling details of the actual war in the background disrupt their experience.

The plot, then, follows the experiences of William James, a bomb-disposal expert in the US Army, and the other two members of his three-man bomb disposal unit, Sanborn and Eldridge, as they diffuse bombs and encounter anonymous 'insurgents' in and around Baghdad across a period of several months. When James arrives in Baghdad and joins the unit at the beginning of the film, Sanborn and Eldridge are initially wary of his cavalier tactics and lack of concern for danger – James repeatedly refuses to follow military protocol, instead running into dangerous situations like a cowboy with guns blazing. Through a series of firefights and 'adventures', however, they come to develop a certain respect for James and his lack of fear.

The film's main focus is James and his need for excitement: the film opens with a quote from journalist Chris Hedges: "The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug." The viewer then watches James as he repeatedly searches for yet another adrenaline-rush, whether it be diffusing a car bomb, firing at 'bad guys', or goading his own fellow soldiers to try to kill him. The film ends with James leaving the 'mundane' safety of America to begin yet another tour of duty in Iraq, and the last scene shows him in his bomb-disposal gear, walking towards yet another bomb as rock-and-roll music wails in the background. The purpose of the film is clear: it is not a serious attempt to deal with the issues of war, the occupation of Iraq, or their disastrous consequences; instead, it is intended to be a fantasy about an adrenaline junky, with war dressed up as typical Hollywood action and adventure.

One of the most telling things about the film is the cold reception it has received even from US soldiers who have actually served in Iraq. These women and men, who are overwhelmingly from working-class backgrounds and largely entered the military out of financial necessity, found the film to be ridiculously inaccurate, portraying soldiers as 'cowboys' who run after adventure. The entire film is overloaded with testosterone: its macho main character, the cowboy antics, the adventurism – none of which is real according to actual American soldiers. Furthermore, there is not a single female character in the film, despite the fact that women are hugely present both in the American military, not to mention the Iraqi populace – it is Iraqi women who bear the brunt of coping with the occupation, and who are the victims of violence whether in the form of bombs or in the form of indiscriminate shootings by contractors like Blackwater.

There is not a single Iraqi character in the film; rather, the Iraqis we see in the movie are nameless, two-dimensional cut-outs that form the 'backdrop' of the American soldiers' actions. They are bystanders, salesmen, drivers, gawkers, and – most importantly – terrorists, insurgents, 'bad guys'. But not a single one of them can be called a 'character', a full-fledged human being with a mind and heart. They are inscrutable, talking in a strange language and usually expressing no emotion. And they are all the same: the main character, James, can not even recognize the Iraqi boy who sells him cigarettes every day on the American military base. Thus the Iraqis in the film can easily be divided into three types: the terrorists (often masked and almost always turbaned), the stern-looking mustached male bystanders, and the anonymous Iraqi women in burqa. There is no attempt in the film to engage with the daily violence, scarcity, and deprivation that have become a fact of life in Iraq since the American invasion and occupation, let alone touch the issues of war-profiteering and economic domination that lie behind them. If anything, The Hurt Locker, with its depiction of nameless, faceless masses of Iraqis in the background as American soldiers fight the 'bad guys' only perpetuates the myth that the US presence is Iraq is intended to 'liberate' the Iraqi people from the chaos of 'terrorism'.

It there is one memorable scene in the entire film, it is when James, having completed his tour of duty in Iraq, returns home to the US, only to find himself completely alienated by its overwhelming consumerism: having spent the past year in Baghdad facing danger and discomfort daily, he now walks the aisles of an American supermarket, disoriented by the literally hundreds of choices of breakfast cereal and every other product. But instead of using this contrast as an opportunity to reveal the economic inequalities that the war is intended to perpetuate, the bizarre contradictions of American capitalism and its imperial aspirations, or even the damaging psychological effects of war on the working-class American soldiers who are forced to fight it (and whose demands for help are frequently ignored by the American military and government), the clean orderliness of the American supermarket simply becomes another reason for action-addict James to return to his adventures in Iraq.

In The Hurt Locker, the war and occupation is nothing more than a two-dimensional backdrop for a study of the surfer-dude action-addict mentality. (And even on that count avoids dealing with the dangerous realities of such a mentality: this kind of cavalier adventurism is exactly what we saw in the actions of the two American military pilots who were recently exposed by footage released by Wikileaks as they laughed and joked while firing on unarmed civilians-- including Iraqi journalists-- from their helicopters earlier this year.)