Taking that piece of historical wisdom, the current strife in Kashmir is, at heart, also about the battle over the content and essence of Indian polity and democracy. Without much hyperbole, India is facing an uprising in Kashmir. Or, at least, the latest outburst in Kashmir’s contemporary narrative of rage and resistance.

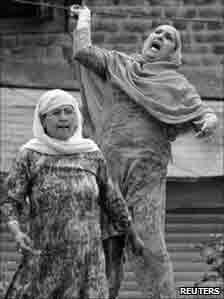

And, like before, like always, the state has so far responded with brute force. The sole departure from the past being that both the sheer intensity of the protests and the exceptional brutality of the response — given that it is mostly children and teenagers who have been gunned down — seems to have taken even certain sections within Indian society by surprise.

The big question, however, is whether New Delhi realises that something new, a potent political challenge, has arisen in Kashmir, and whether the response now will be political or, in continuing mutilation of Indian democratic principles, purely based on disciplining and punishing Kashmiris.

For that, in effect, is what the situation is on the ground. If one were to take the eruption of the militancy in 1989 as the starting point, through the years of the armed forces re-establishing and asserting their supremacy, and the gradual shifting of Kashmiri resistance on to a political terrain, New Delhi’s overall response could well be termed one of the longest pacification campaigns of the century.

But that has certainly not lessened the political reality, the political problem, which lies at the heart of the Kashmir issue and is one of the main reasons for the emergence of the phenomenon of an intifada-like situation in the Valley. Indeed, recent events have highlighted the limitations and sheer myopia of total and utter reliance on force to deal with protests in Kashmir.

Despite the presence of overwhelming force and coercion, Kashmiri protestors persevered. This not only threw the state government into crisis, but also forced a virtual closing of ranks among the separatist leadership, while firmly bringing back the sentiment for azadi centrestage.

Now that that slogan is once again the main rallying cry in the Valley, New Delhi must ponder just what two decades of a massive counter-insurgency effort has yielded.

Of course, the protests have an immediate catalyst. The unabated killing of civilians has been fuelling the rage in the streets on a day-to-day basis. And it’s not even as if bullets and teargas canisters aimed at the upper part of the body are the sole methods of causing fatalities.

A few days ago, a seven-year-old boy was bludgeoned to death by the police and paramilitary forces in Srinagar — literally pulped to death by lathis and rifle butts. Faced with that sort of savagery, with not much by way of condemnation or concern expressed by Indian civil society at large — leave alone a state government seen as the instrument of a wider policy to curb protests and dissent at all costs — vast sections of Kashmiris seem to have relapsed into a firm belief that only by continuing such protests, despite the enormously high costs entailed, can they force some sort of political breakthrough.

That desperate thinking and situation is also a manifestation of a wider failure to actually try and comprehend contemporary Kashmir. The security paradigm in the state operates on the principle of force and fear, the belief that a Kashmiri can neither understand any other language nor be controlled by any other means.

This wholly negates or prevents the state from realising that the years of strife and violence have bred a generation of Kashmiris that is politically aware, conscious of the rupture between the state’s discourse of rights and citizenship and the daily violence and denial of those rights in their own lives.

This generation, weaned on a constant state of violence, also seems to have internalised it, and somewhat transcended the elementary fear it normally generates. Their desperate fight, as it were, isn’t merely against that violence. The stone-pelting isn’t just a reaction to the structural violence that permeates their lives.

The protests aren’t only about staking claim to the rights that a professedly democratic entity offers its citizens. Rather, they are also about the deep-rooted desire of the Kashmiris for a resolution, a political resolution, for their long-festering problems.

The protests are also about resisting the obfuscations, the dissembling that accompanies the denial of that political reality in Kashmir. The new generation of Kashmiris is perfectly aware of how official narratives, ably assisted by an overtly nationalistic media, twist and distort their realities, of how there is a constant delegitimisation of the causes, means and forms of expression of their political reality.

For them, the insanity of the police or the CRPF repeatedly, day after day, shooting to kill — even as the most basic of security doctrines and methodologies would aver that the sort of protests seen in Kashmir do not warrant firing bullets — isn’t some temporary, aberrant reaction.

Rather, it is seen as the official, sanctioned, and thought-out reaction by a state out to wholly suppress them. That awareness or line of thinking has also peculiarly, though not un-understandably, led to a stiffening and hardening of their will to resist.

Given all that, it is a moot point whether the strife and violence in Kashmir will end. It certainly may happen, given the overwhelming nature of the security apparatus, that the protests are quelled for now. But that will again prove a temporary measure, an enforced peace waiting for the next event to rupture it again.

Any incipient moves to break this cycle also cannot realistically emerge from Kashmir. That responsibility lies primarily with the state. With the elements within the political class which, aware of the depth of the problem, might genuinely seek a political resolution, some form of a dialogue.

Elements who realise the mutilation of democracy of the very fabric of Indian society that is entailed in using such force upon a population. The results of a genuine effort on that front might be surprising.

For, one of the best-kept secrets is that were such a process to emerge, with real intent, the average Kashmiri would probably prove to be far more flexible in seeking political solutions than what the images of an enraged mob suggest.