ARTICLE

Legacy of Rabindranath :

Discard the Dead, Uphold the Living

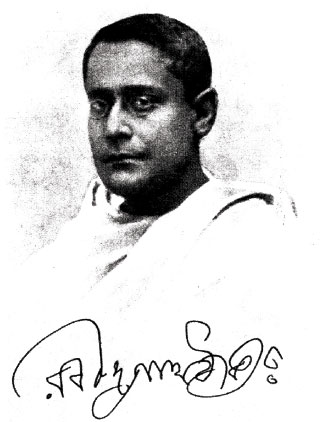

[On the occasion of the 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Thakur (May 8, 1861 -- August 7, 1941) Liberation pays tribute to the great Indian internationalist and humanist. Here we bring you the first part of a three-part article in which Arindam Sen tries to understand the poet's political personality as revealed in his works and in his actual role at important junctures in national and international politics.]

"The wheels of Fate will someday compel the English to give up their Indian empire. But what kind of India will they leave behind, what stark misery? When the stream of their centuries-old administration runs dry at last, what a waste of mud and filth they will leave behind them! I had at one time believed that the springs of civilization would issue out of the heart of Europe. But today when I am about to quit the world that faith has gone bankrupt altogether.

As I look around I see the crumbling ruins of a proud civilization strewn like a vast heap of futility. And yet I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man. I would rather look forward to the opening of a new chapter in history after the cataclysm is over and the atmosphere rendered clean with the spirit of service and sacrifice. Perhaps that dawn will come from this horizon, from the East where the sun rises. A day will come when unvanquished Man will retrace his path of conquest, despite all barriers, to win back his lost human heritage.

“Before I leave let me declare: the day has come when it will be proved that the power craziness and insolence of even the superpowers are now at peril …”

Crisis in Civilisation (1941)

Here we hear one of the most beautiful minds of modern India taking leave of his country, his people, his beloved mother Earth. The text of this address (available in English) delivered on the poet's 80th -- and last, barely three months before his death -- birth anniversary is worth reading in full. For here Rabindranath honestly and brilliantly sums up the lessons he learned in the age of imperialist decadence, world wars and the rise of socialism. Speaking at a time when Hitler had occupied practically all of Continental Europe and seemed irresistible, he declares with profound conviction the inevitable victory of humankind in the battle against forces of reaction and welcomes the approaching daybreak after a long dark night soaked in blood.

But here we see the poet at the summit; let us begin at the beginning.

The Making of Rabindranath

Grandson of Prince (a title procured by bribing the British authorities) Dwarakanath Thakur, a versatile entrepreneur and landlord, and son of Maharshi (meaning great sage, as he was respectfully called in recognition of his religious accomplishments) Devendranath, Rabindranath grew up in a family that owed its prosperity entirely to the British Raj.1 The Thakur Badi (House of Thakurs) was a major centre of the so-called Bengal Renaissance with all its typical features and a foremost cultural centre pulsating with all kinds of creative pursuits. Raja Rammohan Roy, socio-religious reformer and one of the most trusted friends of the British, was probably the greatest influence on the family. Devendranath was one of the leading lights of the Bramho Samaj founded by Roy, and Rabindranath became its secretary when he was 23.

The Insulted

(excerpts)

O my unfortunate country, those whom you have insulted

They will drag you down to their own level,

Those whom you have deprived of their human rights

Those who stand before but find no place in your lap

They will drag you down to their own level.4 |

"Our Bramho family", he later wrote, "had dissociated itself from the complex web of all those compulsory rituals of the Hindus. And precisely because of that distance, I believe, my seniors cherished boundless admiration for the universal eternal ideas of India ... a great enthusiasm for reforming the religion of India in conformity with the noblest ideas of India herself, was always present in our family." This atmosphere, he added, taught him a lesson he followed all through his life: valuable things found outside one's natural self should never be imitated or copied, they should be accepted only if and when one can really internalise and assimilate these.2 And for Rabindranath this natural self was moulded above all by the Upanishads, which he loved to recite from his boyhood days, and in this inner world “Western materialist philosophy” – including Marxism, naturally – was hardly allowed entry.

At the same time, the Thakur family was very much receptive to the liberal ideas of European Enlightenment and was wide awake to the latest in Western science, art and literature. An intense effort to combine the best of both worlds, of tradition and modernity or East and West, supplied a basic dynamic to the entire course of the poet’s intellectual evolution, with the two sides often pulling him in opposite directions. The young Rabindranath was primarily a modern rationalist fighting against superstitions, retrograde customs in family and society, and for women’s education and liberty. On these questions he entered into polemics with stalwarts like his eldest brother Dwijendranath, the erudite editor of Bharati magazine, Bankimchandra and many others. However, his perception of Indianness was thoroughly permeated with Hindu religiosity in its purified or Bramho form. In an article on Rammohan Roy (1885) he wrote: “It is in Brahma alone – and not in Jehovah or God or Allah – that Bharatbarsha has searched and found her eternal abode.” (CW volume 11, p 427). Gradually, almost inevitably, this tendency became stronger and by the turn of the century (that is, around the time he turned 40) partly merged into the growing Hindu revivalist trend. In 1901 he founded the brahmacharyashram (mark the pronounced Hindu name) also called ashram vidyalaya in Shantiniketan modeled on the ideals of ancient tapovan ashrams. Here he formally accepted the title of Gurudev and declared that the vidyalaya must be run according to the rules of Hindu sanhitas.3 Around this time Rabi Thakur (as he was better known in Bengal) supported the Varnashram dharma in a number of essays. On a more personal note, in 1901 he married off his two daughters at the age of eleven-and-half years and fourteen years respectively -- and that with dowries far exceeding the Thakur family norm, thereby risking the annoyance of his father -- conveniently forgetting his earlier statements against child marriage.

To Pratima Thakur

Deep distaste for the personal extravagance of rich families now fills my mind.... May we never again have to burden the poor tenants on the land for maintaining us in food and comfort. I have been saying this for such a long time. It has been my hope that our zamindary should belong to the peasants themselves, we should be their trustees. Some allowance for livelihood we can claim from them, but only as their partners. ... What I had aspired to for long, Russia has realised in practice; that I could not achieve this makes me sad. But it will be shameful if we give up the attempt. Even though my youthful ideal has not been fully realised in Sriniketan and Shantiniketan, there I have widened the path towards it.... For our tenants, too, the old pain lingers in my mind. Shall I not succeed in opening the path for them as well before my death?9 |

Rabindranath began to emerge, very slowly and not without occasional relapses, out of this pronounced Hindu revivalist trend during the period of writing his best novel Gora (1907-10). By this time the Maharshi had died (in 1905) and the communal clashes that ensued in the wake of the Swadeshi movement sensitised him to the dangers of fundamentalism and the need of Hindu-Muslim unity. Already in 1910 he composed the famous poem "The Insulted" (Gitanjali, see box); in the 1920s and especially after the Soviet tour in 1930, he basically regained his progressive mental make-up and that on a higher plane. Thus in 1922 he characterised the "Hindu era" as an "age of reaction" when Brahmanism was deliberately built up as a fortification of rituals (Hindumusalman, CW volume 13, p 357). He was even more forthright in a letter written in 1933. Criticising the harsh pungency of modern "Hinduani", he upheld the India of Mahabharata as the true, eternal India as opposed to the fastidious, rickety, ritualistic order of the Manusanhita and Raghunandan (a 16th century arch conservative Hindu scholar from Nabadwip in Bengal)5. In another letter written at the end of 1932 he examined the tradition-modernity interface from another angle and came up with a definitive statement:

"Our mind belongs to our homeland, but our era does not. If we fail to combine the two, we shall remain laggards forever. It is no use complaining against your time or era, because it is more powerful than you are."6

Closely connected to the tension between tradition and modernity, between conservatism and liberalism, was the love-hate relationship with the colonial rulers, seen as both a vehicle of civilisation and an oppressor. To reconcile the opposites and console himself (and his readers) Rabindranath put forward a thesis of the “Small English" vis-à-vis the "Great English" where the former referred to the oppressive officials posted in India and the latter to the English in England -- creators of some of the best in arts and sciences and promoters of liberal humanist ideals. Such an artificial, illusory division served to apparently justify the poet's unquestioned acceptance of the legitimacy and even necessity of the colonial government as well as his occasional outbursts against the wrongdoings of the same government.

The love-hate attitude was shared by many other eminent Indians of the time; what gave it a unique texture to the poet's world was the tension between his hereditary class position and his chosen calling, between "zamindary, my occupation by birth" and "asmandary,7 the profession intrinsic to my nature", as he put it. It'll be interesting to note that he got the opportunity to intimately know village life only as a landlord touring the family estates and wrote most of his short stories on the basis of this experience. His father and eldest brother had been among the most oppressive landlords of the time. The Thakur estates were among the main targets of the peasant uprising that broke out in Pabna district (now in Bangladesh) when Rabindranath was 12 years old. As a landlord Rabindranath adopted some welfare measures and tried to give landlordism a benevolent facelift also in theory.8

At the same time he found ways to enhance the collections from Ryots – naturally in the face of opposition from them – and to expand the estates. In stories, letters and essays he loved to portray the peasants as helpless ignoramuses, completely forgetting (or should we say suppressing?) recent facts of powerful peasant movements, including the one in Pabna. And when in mid-1920s peasants in certain pockets of East Bengal took to the path of struggle and some educated people supported them, the otherwise kind-hearted zamidarbabu came out in his true class colours. In The Ryots’ Tale he vehemently attacked such efforts as dangerous imitation of European concepts like "socialism, communism, syndicalism". In this article he almost accepted, in principle, the tiller's title to land but then opposed it citing practical difficulties. However, for his tenants he had very genuine feelings which multiplied following his "pilgrimage" to Russia (see box: letter to his daughter-in-law written in 1930).

Political Approach to the Raj

The three areas of unity and struggle of opposites discussed above strongly influenced the evolution of the poet's political views through different stages in his life.

He recited his first political poem in the Hindu Mela at the age of 15. A grand Darbar was held in Delhi on 1 January 1877 to proclaim Queen Victoria "Empress of India", even as the country was reeling under the impact of a bad famine. Big zamindars, Rajas and Princes thronged the Darbar with gifts and loud words of glory for the British. Disgusted, the poet wrote, "Let others sing proclaiming the British victory, we should not sing merrily. Come, let us sing a different song..." As he turned 20, Rabindranath wrote a number of articles in Bharati magazine sharply criticising the British and pouring pungent satire on the Indian bootlickers. In Chine Maraner Byabsa (Death Traffic in China) he vehemently condemned the British for opium trade with China and India:

"... owing to selfishness and greed for money on the part of Great Britain, millions of the Chinese people are drifting towards political and social destructions.... It is changing the beautiful country of Assam into a desolate wilderness... It is making the noble Assamese race the most dishonourable and servile people."

The angry young Indian continues, sarcastically commenting on the British claim of being a kind-hearted Christian nation:

"These 'Christians' have exterminated the aboriginal Americans. By their 'Christian' method, they confiscate 'heathen' lands, whenever their covetous eyes fall on them."

The sarcastic tone continued through articles like Dayalu Mangsashi (The Kind Carnivore) Town Hal-er Tamasha (The Fun at Town Hall) etc. In Hate Kalame (By Direct Practice, 1884) Rabindranath expresses deep anguish over the utter humiliation regularly inflicted on Indians and opines that the real prosperity of the country will begin only when the people will stand up against the whims and caprices of the Englishman in their day-to-day behaviour.

In these early essays there was no concept of ousting the colonial power, but the anger was very palpable and there was no word of praise for the government. From the 1890s, (incidentally, this was when Rabindranath was entrusted with the responsibility of looking after the family estates) his intellectual evolution slowly entered a new phase. He envisioned India's past, present and future through the lens of the Upanishads and arrived at a composite historical, social and political understanding that was perfectly in sync with his class standing, his own kind of patriotism and his poetic temperament, but completely at odds with reality. He imagined a golden past when society, instead of depending on state power, took good care of itself. The rich contributed generously to public welfare and basic needs of all were generally fulfilled. Longing to recreate this past, he called upon his countrymen to concentrate on village regeneration – for here lay true swaraj, he declared – rather than trying to "prematurely" drive out the English. "Our real problem in India", he asserted, "is not political. It is social."10

From this perspective, Rabi Thakur entered into polemics with many of his contemporaries. In 1903 he criticised Bepin Chandra Pal who in his magazine New Age called upon his countrymen to answer every blow of the English with a counter blow. This won't do, argued Rabindranath, for this went against the culture of Indians, who were gentle and courteous by nature. Moreover, trying to judge and punish others, one may turn into a hooligan oneself. So one should follow the path of virtue, however difficult it might be. He wrote these polemical pieces11 in 1903; next year he came up with Swadeshi Samaj (CW volume 12) – his most elaborate blueprint for self-reliant development shunning politics. In terms of abstract principles and ideas it was a splendid document, but thoroughly unrealistic and apolitical; in fact it was a call for diverting the people's energies from freedom struggle to an imaginary "self-governance" through constructive work. The author himself was the only person to give the plan a serious trial in his estate at Birahimpur; what he got was little success and a lot of police interference.

Rabindranath's thesis of long-term social work bypassing the question of political power came in for sharp criticism from many of his contemporaries. "To attempt social reform, industrial expansion, the moral improvement of the race", wrote Aurobindo Ghosh, “without aiming first and foremost at political freedom is the very height of ignorance and futility."12 Ramendrasundar Trivedi pointed out that "as long as the bayonet of the English will remain behind the commercial policy" and other policies of the English, little can be done even in realms like industry and education.13

Not ready to change or modify his views, Rabi Thakur went ahead to say that the English are a godsend to satisfy our need for "exchanges of knowledge, love and work with the universal man" (Prachya and Pratichya or The West and the East (1908)). He also asserted that British rule is serving a great purpose by unifying the different nationalities and they should stay as long as this purpose is not fulfilled (Path O Patheya or The Path and the Resources (1908, CW volume 12).

Another justification for the advocacy of unity with the English was derived from the poet’s fanciful projection of the past on to the present. Since India had long been a melting pot of many nationalities, races and religions, with many of them coming from across the borders, he believed that Indians should cherish this spirit of unity in diversity to the British invaders too. In Rakhi Utsav or The Rakhi Ceremony (1909) he wrote,

"The East and the West, kings and subjects – India has been continuously trying to attract all to a field of unity in spite of all kinds of adversities. This is her religion, this is her mission. ... There is a command on us that we shall absorb also those who have come to hurt us.... We cannot drive out any of them who have been invited by God to India's place of sacrifice." The same sentiment was expressed also in his famous poem Bharattirtha or the Indian pilgrimage (1910, Gitanjali).

In most of the essays mentioned above and in Thakur's other works, it is necessary to note, we also find lots of sharp criticism and sarcastic comments against the Raj and he took a frontal role in mass movements on certain particular issues, as we shall see in the second part of this article. To be brief, we can say he was for a "civilised relationship"14 between "the rulers and the ruled" – where both sides should perform their duties and maintain restraint – and criticised both for indulgence in "extremism" ("atishaya pantha"). Remaining within this general political framework, he produced a large number of works, mostly in verse, which immensely encouraged political activists and the masses in their struggle for independence. Emotionally no less inspiring was his own concept of spiritual freedom and moral development:

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action---

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

[Gitanjali, poem number 35, English edition]

(To be continued)

Endnotes

1. Nilmoni Thakur founded the Thakur family at Jorasanko, Calcutta, in 1784 and nine years later the government enacted the Permanent Settlement to build a perpetually loyal social base to counter the growing disgruntlement of the rural poor as manifested in a series of peasant and tribal revolts. Under the new rules and arrangements, a section of pre-British zamindars failed to pay up their dues to the government and had to sell their estates, or parts thereof, to members of the of upstart moneyed class -- different types of comprador elements, brokers, agents, pretty bankers -- many of whom were also landlords themselves. Dwarakanath -- a perfect comprador (junior partner in Mackintosh Company, Carr Tagore and Company, etc) and a Dewan or collector in 24 Parganas, well-conversant with land revenue laws -- utilised this opportunity to the hilt and emerged as a member of the new landed aristocracy. He was also a banker, owner of a coal mine, indigo planter and owner of indigo factories. After him, Devendranath and his eldest son Dwijendranath managed and expanded the estates with typical highhandedness.

2. Rabindranath Thakur-er Rashtranaitik Mat (Political Views of Rabindranath Thakur), Collected Works published by Government of West Bengal, 1961; Volume 13 (henceforth all references to CW will mean this 15- volume edition)

3. He ruled, for example, that students should extend their pranams to Brahmin teachers by touching their feet, while for non-Brahmin teachers a namaskar with folded hands would be considered sufficient. Cast-segregation in matters of dining etc was also accepted.

4. Gitanjali, poem number 108, Bengali edition

5. Chithipatra (Letters) pp 204-05

6. ibid, p 190

7. A play on words: asman refers to the blue heavens away from zamin or the Earth; where zamindary means landlordism, asmandary should signify cultivation of lofty ideas and dreams. See Ryot-er katha or The Ryots’ Tale (1926, CW volume 13, p 347)

8. For example, he glorified Punyaha (the day of ceremonial opening of new account books in a zamindary estate when the landlord himself receives rents from assembled tenants) in these words: "one possesses land and the other is paying for it -- the ashamed human spirit tries to impose an emotional beauty on this dry contract. It intends [through Punyaha -- A Sen] to explain that this is not a contract, that there is a freedom of love in it. The relation between the landlord and the tenant is a relation based on emotion, so exchange of emotions is the duty of their hearts.... The village flute tries to express as much as possible that today is the day for unity between our landlord and tenants." (CW volume 14 p 635)

9. Letters from Russia, Visva Bharati, 1961 edition, p 157

10. Nationalism, Macmillan, 1953 edition, p 97. By "social" the writer means caste and communal divisions, superstitions and lack of education, health and sanitation problems, etc.

11. Rajkutumba (The King's Relative) and Ghusha-ghushi (Exchange of Blows) -- both in CW vol 12

12. From Doctrine of Passive Resistance, p 3

13. Byadhi O Pratikar (The Disease and the Remedy) Prabasi, Aswin 1314 B.S. (1947)

14. See for example Safalatar Sadupaye or An Honest Means for Success (1905, CW volume 12)