Nonadanga Movement

Changing face of Paribartan

Dwaipayan

“There is no place for poor people in Didi’s London” - Purna Das, victim and protester of KMDA’s eviction drive in Nonadanga.

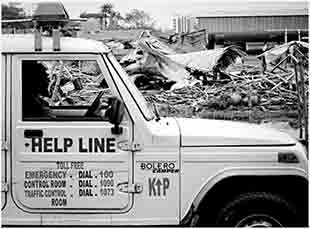

After 10 months of ‘paribartan’ (meaning change in Bengali), the TMC government has done a volte-face on the issues of land-grab, displacement, and government’s brutal reaction to an anti-eviction movement. In their election manifesto they had promised to build 10 lakh housings for slum dwellers and other downtrodden urban poor. “The evictees will get justice, and social infrastructural support”, read another promise in the same manifesto. But recent evictees of Nonadanga and street-vendors from various parts of the city have come to learn otherwise. In 2011, hawkers from Manglahat in Howrah, and those near Big Bazar in Sealdah were evicted. 2012 saw eviction drives in Howrah Maidan and VIP Bazar (near the E. M. Bypass in Kolkata) where over 3000 street vendors were thrown off-street. In continuation, on the 30th of March, Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority (KMDA) bulldozed three settlements in Nonadanga in the locality of Kasba - comprising of approximately 94 huts in Mazdoor Pally, 47 in Shramik Colony and 40 in Subhash Pally. “The government demolished our homes. We, the evictees of the Nonadanga slum, are spending our days and nights under the open sky. We want rehabilitation. Stand with us,” reads a banner of the evictees who have been fighting under the “Ucched Pratirodh Committee” (Committee to Resist Eviction) ever since. Since the first organized demolition drive, they have braved FIRs, police brutalities and repeated attempts at forcibly clearing the area in question. Galvanizing support from various left and democratic quarters, the Nonadanga movement has metamorphosed into a major social issue in Bengal.

Why Nonadanga?

The land surrounding the eviction site in Nonadanga is currently home to around 14,000 settlers who were earlier evicted from various parts of Kolkata, and who after a long and arduous struggle for housing, were rehabilitated in the area under the Basic Services for the Urban Poor (BSUP) scheme. Thus, slum dwellers uprooted from several eviction drives during the Left Front (LF) regime, found a roof over their head in one of the 100 sq. ft. rehabilitation flats constructed by the KMDA in Nonadanga. Under the BSUP scheme, the settlers were entitled to basic civic amenities like proper drainage, sanitation, lighting, community halls, schools and crèche, but in reality they were dumped in the middle-of-nowhere, in what used to be the periphery of the city proper, and have been living under wretched conditions. In any case, as a result of the government’s urban policy, Nonadanga eventually became sort of a refuge for uprooted people from everywhere. Gradually, more and more homeless people - many of them victims of the ‘Aila’ storm affecting the Sunderbans - gathered near the resettlement flats in Nonadanga and set up shanties. The victims of the recent demolition drive were among these unfortunate later settlers.

Most of the residents and later settlers of Nonadanga provide indispensable and cheap services to the middle and upper class of the city. They pull rickshaws, work as domestic help, as petty mechanics and plumbers, and run small roadside stalls. Their services are invaluable for the city’s economy. However even their basic rights to housing, leave alone their rights to health and education for children, remain unrecognized. They are pretty much left at the mercy of KMDA’s bulldozers which is ready to evict them from their shanties whenever calls for ‘development’ or ‘beautification’ of the city ring in the ears of the ruling class.

The recent eviction drive in Nonadanga is neither an isolated incident nor entirely unexpected. As the city expanded, the area surrounding the settler colonies no longer remained a peripheral site with respect to the city proper. With the sprouting of private hospitals, schools, and shopping malls catering to the neo-rich, real estate prices have boomed in the area, making land a prized commodity for land-sharks and promoters. Even during the LF rule, the area in question was earmarked for setting up an IT Park. A 32-acre water park was being contemplated near the adjacent Ruby Hospital in Kasba. According to an article published in the Times of India (17th April), one of KMDA’s earlier plans was to auction the land for setting up a specific business park. Of late, that plan has been modified. The land is now slated to be auctioned off on lease to a private developer for 99 years, with no restriction on land use, for any kind of commercial purpose including “residential complexes, budget hotels, shopping malls, multiplexes, restaurants, service apartments and other facilities”.

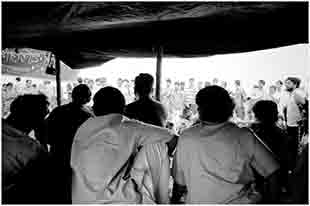

The Resistance Movement

Under constant fear of being evicted, settlers residing in shanty-colonies at Nonadanga had been organizing themselves for some time now. Our party was in solidarity with them from the very beginning. On the fateful 30th of March, about 200 huts were brutally razed to the ground by KMDA bulldozers, as KMDA workers set fire to some houses to further expedite the process. This demolition drive flew in the face of promises made earlier by the Urban Development minister Firhad Hakim and Disaster Management minister Javed Khan assuring the settlers that there would either be no eviction at all, or at the worst, eviction with proper rehabilitation. While one might cringe at the sheer irony of ‘urban development’ and ‘disaster management’ wreaking havoc and arson on the poorest of the poor, the shanty-dwellers were left gaping in disbelief at the complete turnaround from the empty assurances from elected representatives.

They quickly reorganized themselves to resist the eviction and demolition drive. A community kitchen was started, with help from left and democratic forces who stood by them braving physical assault and legal repression. On the 4th of April, Kolkata Police stopped a peaceful protest rally of evictees near the Ruby Hospital junction. Protesters were indiscriminately lathicharged. Rita Patra, a pregnant woman, was injured and had to be hospitalized. A three-year old child, Jai Paswan’s head was fractured by police baton. On 8th, a day-long sit-in demonstration planned at the same Ruby junction was not allowed to take place, in spite of the demonstrators having duly notified the police in advance. Around 69 people were arrested, among them Monika Kumari, a nine-year old child, who had to spend the day in the police lock-up at Lalbazar - a stark reminder of the Payel Bag incident in Singur (2006). Apart from the evictees themselves, various people who came to show solidarity with the struggle, were arrested. Dhiresh Goswami, Kolkata District Secretary of our Party was among the six party members who were arrested that day. When police released the arrested persons on Personal Release bond later that night (around 8:30 pm), it was discovered that 7 of them had not been released. Manas Chatterjee, Kolkata District committee member of our party, and an active organizer of the anti-eviction struggle, was one among them. Others were Partha Sarathi Ray, Siddhartha Gupta, Debalina Chakrabarty, Debjani Ghosh, Samik Chakraborty, and Abhijnan Sarkar - all of them activists with various mass and democratic organizations in the State. The government was quick to invoke the Maoist bogey to justify arrests and several non-bailable charges were slapped on the seven activists, including cases under Sections 353, 332, 141, 143, 148 and 149 of the Indian Penal Code, painting them as ‘anti-national’, even going so far as to ridiculously claim that Nonadanga was used for “stockpiling arms and ammunition”. That the cases were false and concocted with an aim of targeted legal retribution is borne out by an example: the case against Partha Sarathi Ray. On the very day (4th April) that he was alleged by the police to be involved in arms cases and assault on public servants near Nonadanga, there exists documented evidence of him being present in the Indian Institute of Science and Research in Kalyani, a good 70 Kms away from Kolkata.

The severe clampdowns on the protesters on the 4th and 8th were a signature trend of the government’s intolerance towards any organized dissent opposing their anti-people policies. This undemocratic trend was further corroborated the very next day, when 50 protesters were picked up from College Square even before they could start their rally. The trend continued, as on 10th April, 51 CPI-ML(Liberation) members were arrested from Raja Subodh Mallik Square in the same fashion. On the 13th, ruling party goons attacked an assembly of concerned citizens at Jatin Das Park. The group had gathered at the park before proceeding to Alipore Court, where the seven anti-eviction activists under police custody were to appear later that day. Instead of arresting TMC goons who were clearly identified, six protesters were arrested, including Prabir Das, Kolkata District Committee member of our party and Rangta Munshi, Assistant Secretary of APDR. In the evening, concerned intellectuals came together on the streets to lend their support. Famed theatre personalities like Suman Mukhopadhyay and Kaushik Sen, Sunanda Sanyal (educationist), singer Kabir Suman and a host of other civil society activists came out strongly against the high-handedness of the Government. Interestingly, many of them actively supported TMC before they came to power. One of them, Kabir Suman, who was scathing in his attack that day, is one of TMC’s sitting Members of Parliament.

In the meanwhile, people of Nonadanga, who were on an indefinite hunger strike at the eviction site since the 11th of April, continued their protest. On 17th, under mounting pressure from academic and civil society circles (including a letter to the Prime Minister signed by Noam Chomsky and others), Partha Sarathi was released on conditional bail. But the other six activists, including Manas Chatterjee, continue to languish in jail. Government, till date, have shown no sympathy whatsoever to the hunger strikers. Undaunted, the people of Nonadanga, are determined to take the movement forward in the coming days. CPI-ML is committed to stand by them till they achieve their demand of fair rehabilitation. On the coming 26th of April, a massive rally is planned in protest against the government’s urbanization policy of evictions without rehabilitation.

End Note

Ever since Mamata Banerjee’s ascent to the corridors of power, she has been publicly spoken of her fond dream of remodelling Kolkata after the city of London. This oft-proclaimed fantasy has little to do with people-centric and inclusive urban development which is of moot necessity to the hundreds of thousands who continue to flock to Kolkata from villages and suburbs in search of livelihood. This fact is borne out by the KMDA’s budgetary allocation figures published in July last year: “While the budget allocation for maintenance of roads has gone down from Rs 276 crore in 2010-2011 to 180 crore in 2011-12, the amount of slum development has dropped sharply from Rs 129 crore to Rs 84 crore. Funds for disaster management have gone down from Rs 12 crore to Rs 10 crore. Allocation for the health department - which has ambitious reform plans to tackle malaria, dengue and TB - has been cut down from Rs 114 crore to Rs 95 crore.” (Times of India, July 27, 2011.) Thus continuing the legacy of the erstwhile LF government, with promises of paribartan long foregone, Mamata Banerjee’s government treads on a path of urbanization and development heavily skewed against the urban poor and dictated by the terms of neoliberal capital.