ARTICLE

Crisis of Neoliberalism and Challenges before Popular Movements

Concluding instalment of write-up by Arindam Sen, which has also been

published by a booklet with the same title. Continued from Liberation January.

Reagan and Thatcher Kickstart Neoliberal Offensive

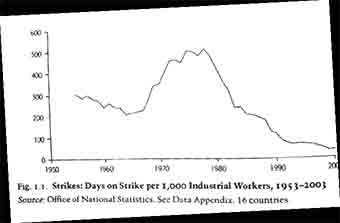

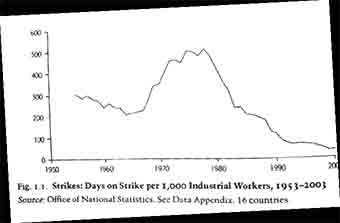

The crisis of 1970s too saw workers fighting valiantly against job cuts, wage freeze despite high inflation (which meant reduced real wages) and other attacks. But they could not hold out for long against organised capitalist offensive with direct state support. This will stand out from the following diagram1 , which shows the longer-run trends in strikes in OECD countries, with year-to-year fluctuations ironed out by using a five-year average. Strikes are measured as days on strike per 1,000 workers in industry:

We can see strikes build up from late 1960s (when the ‘golden age’, also known as the period of post-war compromise, was coming to an end) to mid or late 1970s and then go down a cliff from 1980s. Symbolic of this long downturn were a couple of strike struggles in the two countries from which neoliberalism started its world campaign.

These were the US Air Traffic Controllers’ strike and the UK miners’ strike – recognised as defining moments in the post-1970s American and British workers’ movements. Both ended in defeat and emboldened the Reagan and Thatcher governments to go ahead with their conservative economic programmes, which included wider and largely successful attacks on the rights and pay raises achieved by the working class over the past decades. Having inflicted demoralising defeats on the class enemy, capital upheld Reaganomics and Thatcherism – the first versions of neoliberalism – as the new global model of growth.

The Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) was a powerful union in the US. Their strength lay not in numbers but in the absolutely crucial position they held in running the entire network of air transport and communications. In the 1980 presidential election, this union along with the Teamsters and the Air Line Pilots Association chose to back Republican Party candidate Ronald Reagan, who had endorsed the union and its struggle for better conditions during the election campaign, against Democratic President Jimmy Carter.

On August 3, 1981, the union declared a strike, seeking better working conditions, better pay and a 32-hour workweek. They reported sick to circumvent the federal law against strikes by government unions. President Reagan immediately declared the PATCO strike a “peril to national safety” and ordered them back to work under the terms of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. Simultaneously, replacements (with supervisors, staff personnel, some controllers transferred temporarily from other facilities including the military) and contingency plans were put in place.

Only 1,300 of the nearly 13,000 controllers returned to work. On August 5, Reagan fired the rest and banned them from federal service for life. Several strikers were jailed. The union was fined and eventually made bankrupt. In October 1981 it was decertified from its right to represent workers.

In the wake of the strike and mass firings, the authorities were faced with the task of hiring and training enough controllers to replace those that had been fired, a hard problem to fix as, at the time, it took three years in normal conditions to train a new controller. The government was initially able to have only 50% of flights available. It took closer to ten years before the overall staffing levels returned to normal.

Reagan’s tough handling of the strike even at the cost of much inconvenience to business and general public came in for profuse praise as well as sharp criticism then and later. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said in 2003: “The President invoked the law that striking government employees forfeit their jobs, an action that unsettled those who cynically believed no President would ever uphold that law. President Reagan prevailed, as you know, but far more importantly his action gave weight to the legal right of private employers, previously not fully exercised, to use their own discretion to both hire and discharge workers.” On the 30th anniversary of the historic crackdown, Michael Moore said that Reagan’s firing of the PATCO strikers was the beginning of “America’s downward slide”. He also blamed the AFL-CIO for telling their members to cross the PATCO picket lines. (30 Years Ago Today: The Day the Middle Class Died, by Michael Moore, Daily Koss, Fri Aug 05, 2011). The same year, Oxford University Press published Joseph McCartin’s book, “Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, The Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America”.

No less harsh was Margaret Thatcher, the “Iron Lady” of Great Britain, in dealing with the miners’ challenge.

On 6 March 1984, the National Coal Board announced that the agreement reached after the 1974 strike (which had played a major role in bringing down the Heath government) had become obsolete, and that in order to rationalise government subsidisation of industry they intended to close 20 coal mines. This meant twenty thousand jobs would be lost. Strikes started spontaneously in several threatened mines. On 12 March 1984, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) – one of the strongest unions in the country – declared a national strike and it took effect immediately.

A bit of background information should be in order here. A strike nearly occurred in 1981, when the government had a similar plan to close twenty-three pits, though the threat of a strike was then enough to force the government to back down. In fact, the government decided to avert a strike at that time because coal stocks were low, and a strike would have had a serious effect. Next year, it offered a 5.2 percent raise based partly on increased productivity. Union members accepted it, rejecting their leaders’ call for a strike authorisation. This clever move enabled the government to stockpile enough coal for the inevitable future showdown.

The government was thus in a position to take the strikers head on. On the day after the Orgreave picket of 29 May, which saw five thousand pickets clash violently with police, Thatcher said in a speech: “… what we have got is an attempt to substitute the rule of the mob for the rule of law, and it must not succeed.... The rule of law must prevail over the rule of the mob.”

The impact of the strike was nowhere near as hard-hitting as previous strikes such as those of the early 1970s. With most homes equipped with oil or gas central heating and the railways long since converted to diesel and electricity. The problem of potential power-shortages as a result of a coal strike had been recognised by the Thatcher government which insisted that Britain’s coal-fired power stations create their own stockpiles of coal which would keep them running throughout any industrial action. This strategy turned out to be incredibly successful during the miner’s strike, as the power stations were able to maintain power supplies even through the winter of 1984.

The strike ended on 3 March 1985, nearly a year after it had begun. In order to save the union, the NUM voted, by a tiny margin, to return to work without a new agreement with management.

The 1980s thus marked the onset of neoliberal offensive by pushing its class antagonist into the defensive. Globalisation became the magic word and when the victory sign “TINA” (There Is No Alternative) was flashed in a post-Soviet scenario, many if not most people willy-nilly accepted it.

Popular Rebellions in Latin America

But it was not a permanent defeat; it could not be. Latin America, the first prey of Western neoliberalism in the Third World, saw the first series of sustained and effective rebellions against the menace at the turn of the millennium: the Indian uprising in Ecuador that ousted the neoliberal president; the insurrectionary waves in Argentina that sent successive presidents packing and developed into a revolutionary crisis in 2001-2002; the popular uprising in Venezuela in April 2002 to bring Hugo Chavez back to the presidency after he was ousted in a military coup; the gas war in Bolivia in 2003 which saw the neoliberal president being ousted; and so on.

Compared to the sporadic outbursts we see in our country, these popular movements were much more sustained (not under communist leadership though) and brought to power forces which opposed US hegemony and the neoliberal programme to different degrees. These governments instituted democratic political reforms and partly restored public control over natural resources (Venezuela from 1999, Bolivia in 2006, Ecuador in 2007). Even Kirchner in Argentina had to implement, under popular pressure, certain progressive measures. Some of these countries – most notably Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador – have advanced much further with staggering but persistent experimentations of building some sort of proto-socialist society.

The World Social Forum (January 2001) also emerged from Latin American soil and spread to the rest of the world with the anti-TINA slogan “Another World is Possible”. This was accompanied by massive mobilisations against the WTO, the World Bank, IMF and the G-8 in Seattle, Washington, Prague and Genoa respectively between 1999 and 2001.

These struggles gradually flattened out mainly because they lacked a sense of what was to be done next, and also because they came more and more under control of dubious Western NGOs. The WSF in particular, despite its promising initiation, ended up as a safety valve for letting out some steam of grievances. Having said this, we must affirm that the movements did help heighten popular consciousness and activism. On this grounding there developed the next, present round of confrontations with the neoliberal imperialist order.

Crisis and Class Struggle: Present Trends and Tasks

As on past occasions, the current crisis has been accompanied – or should we say complemented – by powerful mass movements everywhere against job loss, wage freeze, food crisis, price rise, subsidy withdrawal, corporate capture of natural resources as a means of legalised loot, and so on. Let us briefly examine some of the more important dimensions of these political fallouts of the economic crisis.

Lessons of the Occupy Movement

The occupy movement announced the return of agitational politics in the US in the hands of a new generation, and in a changed context, drawing inspiration from the then recent outbursts in Spain, UK and other countries and the concurrent Arab Spring. The strong and clear battle cry “99% against the 1%” reverberated through America and beyond for the better part of 2011, the international year of street protests. It featured a rich variety of issues and forms of struggle. Oakland (USA) for example distinguished itself by organising highly successful dock strikes and blockades – actually it based the movement on concrete demands of the local dockworkers rather than on the general “99%” slogan.

But why target just “1% “? Does the rest belong entirely to the working and middle classes? No, the “99%” does include many rich people. But to pinpoint the “1%” at the top of the economic pyramid is to concentrate fire on those who actually command both the economy and the politics of the United States: those who own controlling stakes in largest corporations and often double up as influential senators, highest campaign contributors, advisers to the President, and so on. As the recently deceased progressive American writer Gore Vidal said in a BBC interview back in July 2002, “One percent owns everything – like the CEOs who now seem to be queuing up to go to gaol! Under them there is a further twenty percent who support the Empire. These are the lawyers, the journalists, politicians and bankers and so on. The one percent hires the twenty percent.”2 By identifying only the 1% as the main enemy, the slogan seeks to neutralize the 20% at this primary stage of struggle.

Anyway, what is the present state of the great social movement? Events like families occupying schools in Oakland to prevent their closure, Occupiers across the country working to prevent evictions and foreclosures, are often reported in the independent (non-mainstream) media. On 17 September, as part of a three-day (15-17) action programme, protesters converged near the New York Stock Exchange to celebrate the first anniversary, marking the day they began camping out in Zuccotti Park. Marches and rallies were organized in several other cities around the world to commemorate the day. People joined concerts. Lectures were delivered. But there is no denying that the very broad movement has fragmented into several mini-movements, with some preoccupied with ecology, some with pressing local problems and so on, rarely coordinating among themselves.

Excerpts from

Progressives Must Move Beyond Occupy

By Cynthia Alvarez3

17 September, 2012 Countercurrents.org

All human organizations must solve this problem: balancing collective authority against assigned authority in leadership. Without leadership and written rules, Occupy cannot take the initiative or go on the attack. The fallacious, impractical, unrealistic elements of Occupy philosophy ensure it will never become a viable Progressive fighting force. Only by rejecting these constraints in favor of organization that facilitates winning will Progressives be able to build a serious engine of societal reform. Serious Occupiers who want to re-form society should move to better-organized Progressive groups. I will subscribe to Occupy networks and might attend Occupy direct actions. But mainly I’ll be looking for other progressive groups who could actually do something. The Green Party, for example, has inspiring leaders and a constructive plan for a “Green New Deal.” Perhaps it’s time to (finally) create a national Progressive Party - an umbrella party for all Progressives that articulates a general Progressive platform and provides the leverage to move national policy. |

What went wrong? One-sided emphasis on political open-endedness, horizontalism in organisation and decision-making by consensus contributed to the initial successes of the movement but prevented it from gaining the sharper political focus and strike power necessary for going over to the new, post-crackdown stage. In the absence of democratically formulated common goals and a unifying centre, the enormous amount of social energy that was mobilised under the “Occupy” banner remained in the nebulous state for far too long, failed to solidify and, with the inevitability of a natural law, got dispersed in a political vacuum.

But energy is never destroyed, it cannot be. It can undergo endless transformations and get condensed into solid mass when certain conditions are present. At the moment part of the occupy energy is working at local levels as indicated earlier; a part goes into higher political actions like protests against NATO and G8 summits; and probably the major part has been inducted into the Obama presidential campaign under the guise of warding off the threat of a more anti-people Republican takeover. However, since the basic source of the movement of 99% – the crisis of neoliberal order making life intolerably harder for the average American – is only going to get worse, it is reasonable to expect that sooner or later the movement will rediscover itself in a new situation in a new format. A lively discussion is going on about what is to done now (see box).

The occupy movement was a spark that did not find the objective and subjective condition to immediately start a prairie fire. But, with all its historical limitations, it’s continuing, even spreading. Many in the movement are proud to see the Jal Satyagraha in Khandwa district in MP district of India and protests against the Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant in TN as part of their struggle; why shouldn’t we?

Workers, Students and Farmers against Neoliberal Offensive

Capital seeks to wriggle out of the crisis and bolster its position and profits by different means affecting different cross sections of people, pushing the latter on to desperate resistance struggles.

Right from the days of the PATCO struggle and the UK coal workers’ strike, the neoliberal state as the agency of capital has been trying to snatch the rights and wage levels gained by the working class through more than a century of bitter struggle at the cost of much blood and sweat. Naturally workers are fighting back everywhere against these “flexible labour policies” and “labour market reforms”. In our country we have witnessed national industrial actions as well as powerful struggles of industrial workers in the Gurgaon-Manesar belt, in Coimbatore and Sriperumbudur in Tamil Nadu and dozens of other places; of construction workers and other sections of casual unorganised workers including growing contingents of women workers; of bank and government employees and so on.

On top of a series of militant movements throughout the world, miners’ strikes in Spain in early 2012 and in South Africa in August – the latter resulting in the death of some 34 workers – won widest popular support at home and abroad. In China, TNCs have long been accustomed to carrying on super exploitation of the super disciplined workforce thanks to the absence of an independent trade union movement, but in recent years workers have started asserting themselves. The massive clash between workers and security guards at a Foxconn plant in September was one of many instances.

Severe cutbacks on education budgets as part of the austerity overdrive and further opening up of the education industry to private profiteers have emerged as major fighting issues before the global academic community including students, teachers (recently in Chicago for example) and others. From UK in 2010-11 through Chile, France and some other countries and this year in Canada students have placed themselves firmly at the forefront of a spreading youth rebellion. The Canadian students have earned widespread support linking their tuition protests to other popular struggles against higher fees for health care, the firing of public sector employees, the closure of factories, new restrictions on union organizing, etc.

Worldwide corporate land and resource grab have brought agriculturists (from big farmers through middle and small peasants to agrarian labourers) and indigenous communities into intense collision course with capital and its state. Struggles against various agro- business companies like Pepsi and Monsanto as well as multinational retail chains like Wal-Mart are also growing.

The Bolivarian Alternative to Neoliberalism

Our survey of struggles against capital in crisis would remain unpardonably incomplete if we did not mention Latin America. Because it is here that long and hard struggles on the streets have culminated in the emergence of popular governments in a number of countries which try and follow heterodox anti-neoliberal economic policies to the extent possible in a hostile US-dominated world economic environment. In Venezuela for example, as James Petras points out, “Despite crime and official inefficiencies and corruption, the Chavez era has been a period extremely favorable for the lower class and sectors of business, commerce and finance. This year – 2012 – is no exception. According to the UN, Venezuela’s growth rate (5%) exceeds that of Argentina (2%), Brazil (1.5%) and Mexico (4%). Private consumption has been the main driver of growth thanks to the growth of labor markets, increased credit and public investment.” (Venezuelan Elections: a Choice and Not an Echo, Oct 4, 2012)

The impressive progress countries like Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador have made and the difficult challenges they face are too vast a subject to be covered here, but certainly they are a great source of inspiration for all who are struggling to break the bondage of capital and move toward a saner society.

BIG Picture and Basic Message

Behind periodic crises – we learned in our brief dialogue with Marx – lurks a complex interplay of myriad forces, the most important being “the epidemic of overproduction” or overaccumulation of capital going hand in hand with increasingly skewed distribution of income and wealth.

Marx developed a perfectly dialectical approach to crises. On one hand, they constitute capitalism’s inbuilt mechanism for spontaneously and ruthlessly eliminating excess or over-accumulated capital, ‘so that the cycle would run its course anew’ (Capital). On the other hand, they achieve this in a manner that ‘paves the way for more extensive and more destructive crises, and diminishes the means whereby crises are prevented’ (Communist Manifesto) and leads finally to the ‘violent overthrow’ of the rule of capital (Grundrisse). It is from this approach that we have tried to comprehend the crisis of neoliberalism.

The central message emanating from the financial catastrophe and its aftermath is that global capitalism’s strategic response to the crisis of 1970s has failed. That was a three-pronged strategy comprising deregulation or market fundamentalism, globalisation and financialisation. Since these were the three pillars on which post-1970s capitalism stood – and, in a certain sense, and in certain parts of the world, flourished – the extensive damage they have suffered have left the whole imposing edifice tottering. This is why there is no end to aftershocks like the European Sovereign Debt Crisis. This is why, full five years after the onset of the crisis, the world economy is still in the doldrums.

But even a systemic crisis like the present one does not necessarily mean that the system is going to collapse anytime soon. However, if past experience is any guide, some sort of restructuring is likely to be in the offing, the basic content and direction (pro- or anti-labour) of which will depend mainly on the outcome of the class battles – defensive and offensive, extra-parliamentary and parliamentary – now raging across the globe. Shall we see a repeat performance of the masses in US and Europe forcing respectively the New Deal and the welfare state policies on their ruling elites? Will the non-financial interests among the bourgeoisie, in league with their farsighted organic intellectuals, assert whatever relative independence they still enjoy to try and put in place regulatory policies and reforms that could salvage some of the lost legitimacy of capitalism? Or will the financial oligarchies succeed in dishing out cosmetic changes in policy that actually consolidate their own hegemonic positions and megaprofits?

No, we must not just wait and see.

As we write these lines, the people of India are up in arms against a booster dose of neoliberal ‘reforms’ administered by Dr. Manmohan Singh and his masters. So are the masses across the world. On 26 September, upwards of 200,000 demonstrators took to the streets of Athens, as part of a general strike. “People, fight, they’re drinking your blood,” protesters chanted as they banged drums. Police clashed with protesters hurling petrol bombs and bottles. The same day, a € 11.5 billion ($14.87 billion) package of spending cuts was announced as demanded by the country’s international lenders. Almost simultaneously, thousands besieged the parliament in Madrid and more than half a million people marched in cities across Portugal to protest against cuts in social security.

All of us must join the fight with all our might, for a rollback of the neoliberal policy regime and progressive reform now and ultimately for a radical transformation of this irrational, oppressive, inhuman social order.